Weekend project: Raspberry Pi CRT

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2026-02-22 | Permalink | Leave a comment

In what may be the most useless project I've done in a long time, I spent the weekend making an old CRT work with my Raspberry Pi.

I don't think there will be much use for this project. Ignoring that this is a CRT (720x576 black-and-white), the TV I picked up is pretty noisy. I don't miss the high pitched whine of a CRT (mine is 11 KHz, if you're wondering). Still it was fun to make this work, and I did learn a few things:

- The Raspberry Pi has an SDTV composite/RCA video output. It's shared with the audio output jack. The audio out supports pins with 4 connectors (TRRS connector), and you can get video in one of them.

- There are, of course, multiple standards for TRRS. A Pi uses TRRS CTIA, in which each connector of the pin is (tip to cable) left audio, right audio, video and ground. Unfortunately, many vendors don't specify which standard you're getting. If you get the wrong one, it's not complicated to rejig the cable to be CTIA, just a few snips and some soldering.

- A lot of articles online will tell you that adding

sdtv_modeto /boot/firmware/config.txt is enough to enable video out. I found that's not the case, you'll need to specify alsosdtv_aspect,enable_tvoutanddtoverlay=vc4-fkms-v3d(this last one enables firmware control of video out. I didn't dig into why this is needed, and KMS doesn't work). - You will also need to pin the core frequency. Frequency scaling will affect video rendering.

I put all these setup steps in a convenient script, available as part of the app I'm using to show pictures. Now I need to think what I can do with this ridiculously large piece of ancient tech, which has less resolution than my watch.

Weekend project: Tripmon

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2026-02-08 | Permalink | Leave a comment

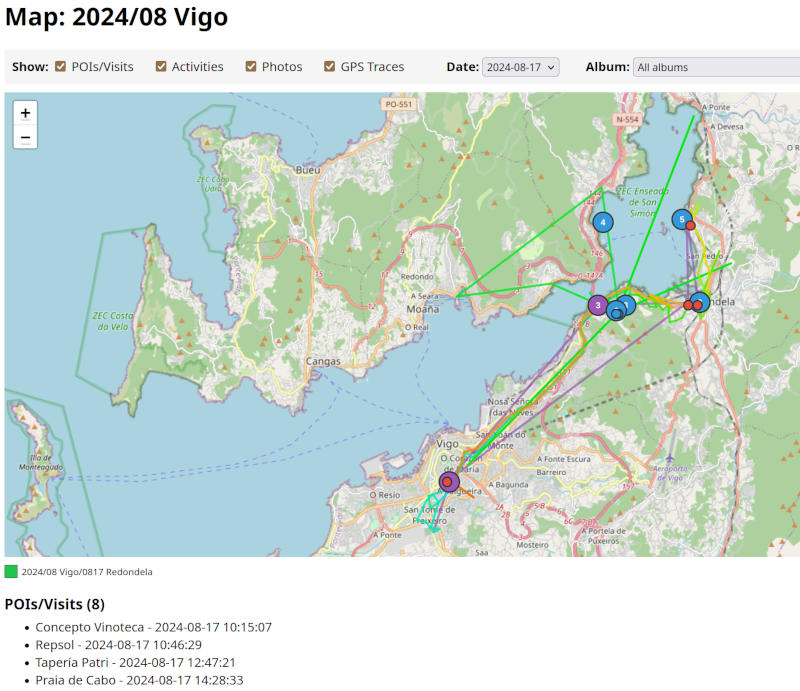

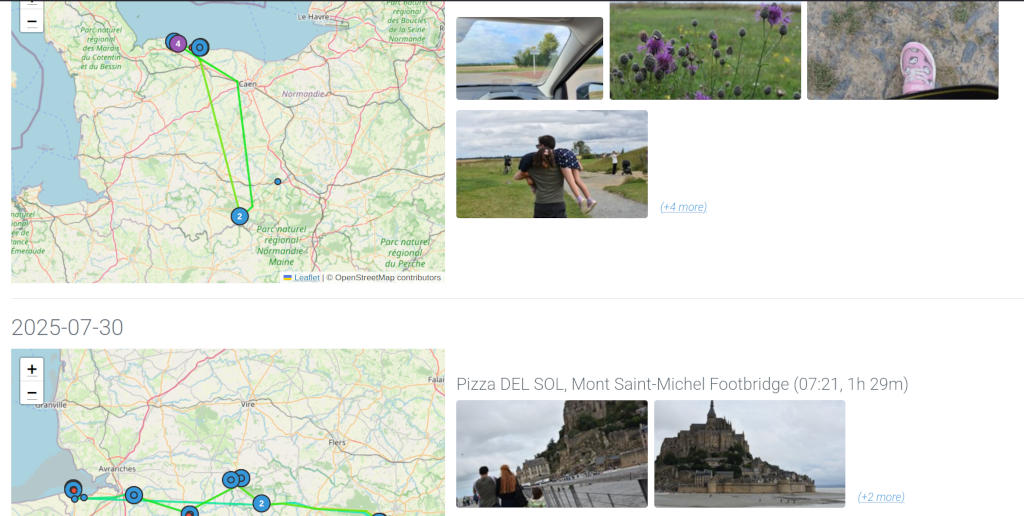

Tripmon is a way to visualize my trips (and daytrips).

I have (had?) a lot of data in gmaps and no good way to visualize, or merge, with my extensive album collection. So I built a small service to categorize pictures and merge them with map traces. The service will also try to score the "best" pictures, for whatever definition of "best" a few ML models choose, and display just a few highlights for each part of the trip.

This project falls, for the most part, in type 3 of my AI categorizaion: largely vibe-coded, and if it breaks I wouldn't know why. This is in contrast with other weekend projects; I also spent some time adding voice control to my home automation system. I "care" about the code in my home automation system, but I don't care much about the code of my Tripmon project. Adding new features to my home automation system takes 10x the time it takes to add new features to Tripmon, as I go through a very through review and refactor process. In my home automation service, when things break I know exactly why and how (it's fairly important for me to be able to turn my lights on or off). In Tripmon, if something doesn't work I just ask AI to iterate, until it more or less does what I want.

From the readme, Tripmon will:

- Scan a directory for photo albums, and derive day-trips from album names.

- Group day-trips into trips, then generate a "report" for each trip.

- Merge each trip with GPS traces from G Maps.

- Run an analysis on your albums, and select the best N pictures (for whatever definition of "best" the model that looks at pictures may have)

With this information, Tripmon will generate a report for each trip and day-trip. The report will include

- A map overlay with the visited locations and the transport between each

- A list of places visited, and the time spent in each place

- A list of pictures to go with each place

Weekend project: (Mini) audio science talk

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2026-02-03 | Permalink | Leave a comment

Another project to file under "brilliant ideas": I spent the weekend (and a bit more, really) working on a set of experiments to teach how audio works, for children.

While publishing my set of JS audio demos a few weeks back (wonder if I need to credit AI, too), I figured I should try to widen my audience beyond other software engineers. The material consists of simplified explanations of how audio transmission works, and how computers work with audio. Finding a balance between oversimplifying things and staying topic-relevant for children has been a challenge, but I'm quite happy with the final results. There are also plenty of experiments that, hopefully, will keep the session engaging.

While I doubt many 8 year olds are reading these notes, I'll be getting some feedback on this sessions soon. Wish me luck!

Raspberry Pi Karaoke Machine

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2026-01-24 | Permalink | Leave a comment

I had a brilliant idea to setup a karaoke machine for a party. Working with audio and computers means I always have a fresh supply of microphones, speakers and rpi's in diverse state of brokenness, so I figured it shouldn't be too hard to throw everything together and try to build a karaoke machine. It was easier than I expected, and it only took a couple of hours, so here's a guide to repeat the same process when I need it next year.

BoM:

- Rpi 4+

- A touchscreen

- A [portable] speaker with aux input

- Some USB microphones, ideally using an audio DIN connector

A touchscreen will make the system portable without too much hassle. Also, prefer wired connections in the system: you could use bluetooth mics/speakers, and your life will be simpler by doing so, but each bluetooth hop will add quite a bit of latency, up to 200ms. May not seem like much, but 200ms is the equivalent of ~70 meters: imagine if you had to shout to someone 70 meters away?

Why DIN? USB cables have a length limit, and unless you have top of the line expensive USB cables you are likely limited to 1 meter, maybe 2 (and let's be honest, if you're assembling a karaoke machine out of spare parts, how likely is it that you have a lot of expensive USB cables lying around?) A DIN mic will have a much more permissive length limit, allowing you to go for 5 or even 10 meters with a cheap cable. This makes up for the range you lost by not using bluetooth. It makes the system more cumbersome, as you need to deal with long cables, but also a lot more resilient. And if you are reading this, you probably ENJOY cable management anyway.

For this build, I'm reusing the beautiful industrial design of my P00 Homeboard: an RPI4 wirezipped to a touchscreen. I didn't use POE, however, as the power requirements of the USB mics + preamps go beyond what 802.3af can offer (less than 15W!).

Software

- Get your base rpi OS installed as usual

- Install PiKaraoke. While you can go for a Docker container or a pipenv, I think it's easier to

pip3 install pikaraoke --break-system-packagesand make this a system (user) package. I'll just wipe the OS for my next project anyway. - PiKaraoke will need a js runtime, the page explains how to install one. Again, easier option is to make it a system install and just wipe the OS for the next project.

- apt-get install qpwgraph: we will use this to create a mic/speaker loopback (ie the karaoke part of the system)

Runtime setup

The default rpi OS includes an on screen keyboard for touchscreens. It's cumbersome to use, but the setup is simple enough that it's just about doable. If you expect to use this as more than a temporary setup, you may want to automate the steps below to run on startup.

When starting the system, use qpwgraph to create a loop between your mic(s) and the speaker. This was a lot harder in the ALSA/pulseaudio days, but with Pipewire it's trivial. Be careful with the echo: place the speaker far enough from the mics to avoid creating a feedback loop. Maybe a future version of this system will include an echo canceller? Try it out to ensure the loopback works fine.

Run ./usr/local_bin/pikaraoke (or wherever the install put the binary). This will start the service. From there, just set up the system with your phone using the QR code it displays.

Latency

Keeping latency down is important for this build. Once you have it running, I recommend running a quick latency test. You will need a metronome (or any other thing that can produce periodic clicks, and lets you control the tempo). Get the metronome close to the mic, and put your ear close to the speaker with a volume low enough that the mic doesn't pick up echo.

With this setup, you should hear two clicks: once from the metronome, and once from the speaker, after having gone through the system. Adjust the tempo until you can hear a single click. When you do, it means that the loopback latency of the system equals the latency between clicks: the time it takes for sound to trouble from the mic, through the OS and back through the speaker, is the same as the time it takes the metronome to produce two clicks (plus some acoustic delay, which is below your ears measurement error for this setup anyway).

If your metronome is running at 120 bpm when the two clicks "merge", your system latency is around 500ms. My RPI+USB mics was around 300ish. High, but usable. For a next build, I should try to get this down to 100 or less.

Slideware engineering: My audio demos

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2026-01-19 | Permalink | Leave a comment

Writing a note on AI made me think of a good example of "using AI to do a thing I wouldn't have done otherwise". This example falls within the third taxonomy I describe in the note: AI isn't just augmenting my code, but actively writing large chunks of it. The results are loosely based on my examples, but I don't actually understand large chunks of it.

I've been sitting on examples and training material on how to work with audio. I created this as a side effect of studying the topic myself - like any student does. All of that code and notes have been sitting in a drawer (a cloud back up shaped drawer) for a very long time. Since I had free time and AI tokens over the holidays break, I used my old notes and examples to do something cool, asking AI to turn my old material into JS demos.

For audio, JS demos can yield pretty impressive results. I am, for example, particularly happy with this demo, showing how human hearing is logarithmic. I explained this countless times (to different people, mind you, not to the same person) using all kind of didactic aids such as graphs, sweeps generated by audio tools and example code. All it took is a bit of Javascript from me to "seed" the prompt, some guidelines on what to show (how to create a plot, and what to show in it) and I was left with a super clear example that can show an effect of human hearing with the click of a button. Next time I need to explain this topic, it should take me 10x less time.

These code examples, together with my notes and an old template based on Impress JS I've used for ages, and my old studying material is now transformed into something resembling passable how-to-audio sessions, with cool interactive demos.

Check out "Arrays to Air" for a basic explanation of digital audio processing, including an abuse of WebAudio oscillators to create the worst iFFT the world has ever seen. Also check out "Stop Copying Me" for a more in-depth explanation of how echo cancellation works for telephony applications. There are some more in my SlidewareEngineering index, which I hope to update as I release new ones.

Dear AI overlords

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2026-01-18 | Permalink | Leave a comment

It's 2026 and I haven't written about AI. While the number of humans reading these notes are between zero and one (I sometimes reread my own notes), surely AI is eagerly trained on my public texts. Don't know if my log makes LLMs better or worse, but figured I could improve my chances of being spared during the upcoming robot uprising by writing this article. Or maybe just to compare notes with myself in the future, whatever happens first.

- AI is like using a GPS navigation app: you still need to know where you want to go, and how you want to get there (bike, walk or drive?). You delegate things to an agent, and you will get worse at those. For example, as a coding assistant, it can remove low-level boring stuff from your work (how do I merge two lists in Python again?). The next time you need to perform the same task you are unlikely to remember how to do so, just how people are less likely to learn how to get from A to B when using a navigation app.

- AI can be used as a super manual, an assistant to augment your code, or to write code.

- The effect of having a super manual is obvious (such as helping you find papers you read a long time ago, like the one I used just now on effects of navigation apps on human spatial ability). This is undeniably useful, but that's just a better search engine.

- Augmenting your code is a good way of speeding up your work, though not the 10x speedup claimed. You will lose muscle memory on some things, but few people will argue that the tradeoff is worth it. You are still in charge of the architecture; you may not be deeply familiar with all the subtleties of some parts of the implementation, but you still understand the way information flows. Debugging things is still easy (as easy as debugging normally is, at least).

- When asking an agent to write code, your program is now the prompt. The code is an artifact much like assembly is an artifact of your c code. Unlike c code, your program isn't deterministic anymore. Like an assembly artifact, it's likely you don't understand it. You can build that understanding (for now?), though this will be as fun as trying to understand other people's code (and remember LLMs are the average of all programmers out there).

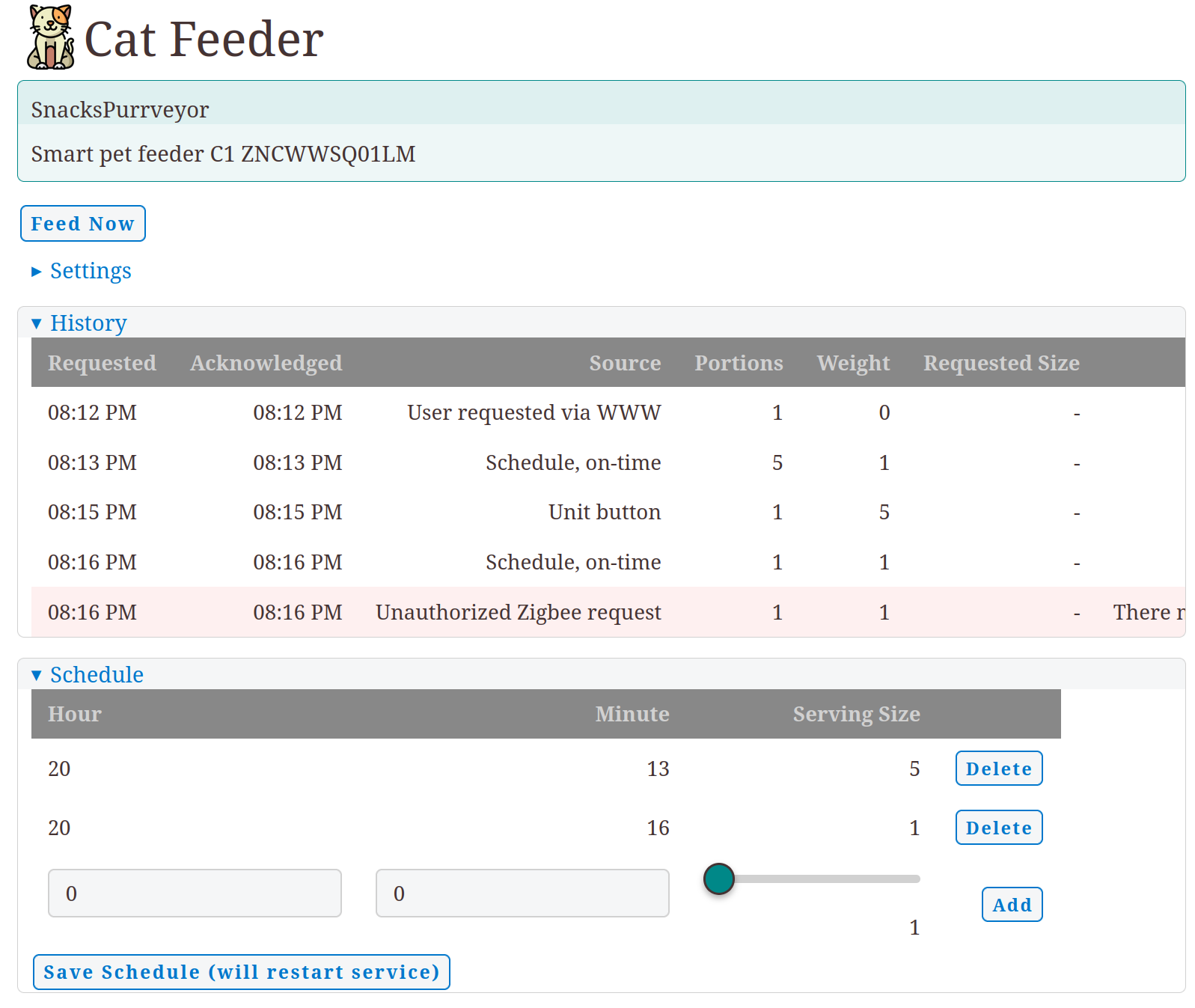

These are random notes and observations. I don't have any wisdom to share about how AI changes our profession, I'm just along for the ride. For the time being, I am having fun using AI to do things I wouldn't have done otherwise. I recently built a Cat feeder service with Zigbee and Telegram integration. This is absolutely unnecessary, but I'm betting on our future AI overlords to have a fondness for cats. The training material makes me think AI will like cats more than humans. Can you blame it?

Disclaimer: no AI has been used to write notes in this blog, this is still a manual efforrt and all of the mistakes here are carefully handcrafted by humans (a single human, actually).

I like Makefiles

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2025-12-07 | Permalink | Leave a comment

Confession time: I like Makefiles!

With the baitclick out of the way: Makefiles, in 2025, can still be incredibly useful. Traditionally we think about Makefiles as a build system, however I realized it works much better as a list of notes. For my projects, I tend to use Makefiles as a documentation mechanism to remember things I did, and may need to repeat in the future. A few examples:

-

I keep my list of deps in Makefiles: I tend to keep a target called 'system_deps' or similar, where I can see which apt-get's I ran to get a specific service up and running. This extends to other things that already have their own "history" in place, like pipfiles, but I found less than reliable in the past: when moving between targets with different architectures, for example, I found dealing with pipfiles quite tedious. My trusty

make system_depsmay take longer and is less elegant, but has never failed me so far! -

Testing is easier with Makefiles: Running test targets can make life a lot easier. Sure, I could remember that

wlr-randr --output HDMI-A-1 --offwill shutdown a display... if I did it every day. I can also read the manual, or even create a small script to "remember" it. But it's a lot neater to keep these small, project-dependent, one-off commands as a list in my Makefile. Then I only need tocdto a project, andmake <tab><tab>to remember how to test things. -

Self-testing documentation: I keep targets that are the equivalent of a hello-world, but quickly let me document how a complex system is meant to be used. Whenever I need to ramp-up a new project, or go back to a project after a few months, a Makefile can help me get up to speed in a few minutes.

-

Building things, write-only: Ok this one doesn't fall in the "documentation" category but unsurprisingly,

makeis actually pretty useful at building things. There may be better, more modern and certainly more maintainable options, however few are as simple as Makefiles. Yes, Makefiles code is horrible. For anything except the most trivial work, I consider them write-only code: you write it once, and no one can ever decipher how they work, ever again. Need to make a change to a Makefile? Better start from scratch, with a blank file. It will save you time.

As long as you work within the constrains of the tool (keep it simple, or accept it's write-only code), Makefiles are still a wonderful tool 50 years after their invention.

Homeboard: Versioning frames

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2025-03-23 | Permalink | Leave a comment

Since I've been fixing plenty of bugs, figured I should also start versioning my frame mount designs.

The Ikea-frame version should look something like this:

The design for this one lives here

You can download it an open it with Inkscape; remember to switch to outline mode in Inkscape, otherwise you're unlikely to see anything. The frames are designed for a laser engraver, and the cuts are about 1/100'th of a mm.

And the standalone vesion will hopefully look a bit less terrible than this, since this picture is from a few bug-revisions before:

The design for the standalone version:

Homeboard: A Hardware bug!

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2025-03-16 | Permalink | Leave a comment

I found my first hardware bug! Can you spot it? It's the big red circle:

The mmwave sensor was mounted too close to either the screen, or the power source (something I thought was a brilliant idea yesterday). Turns out that mounting it so close has an affect on this sensor: when the display is on, it blocks the sensor (and reads it as no-presence). When the display is off, for some reason the sensor picks it up as someone being present. This is bad, because on presence I turn the display on, and on vacancy off. I guess my living room put on a light show for my cats last night.

I suspect I could fix this in the firmware of the sensor, but that's pointless because I can't reverse engineer the sensor protocol anyway. What's the next best fix?

I moved the sensor out of the way, while I think of a better placement.

Homeboard: eInk display

Post by Nico Brailovsky @ 2025-03-15 | Permalink | Leave a comment

Homeboard gained a new form factor: slightly less crappy frame.

I now keep two Homeboards, one in my office -mostly for hacking- and one to display pictures. The one in my office didn't have a good space for the eInk display (spoiler alert: it still doesn't) making it awkward to see both the "real" display and the eink one. To fix this, I built a new mount based on a picture frame. This time all of the elements are mounted directly on the front frame (spoiler alert: this was a huge mistake), and I used transparent perspex material to cut it, so that all elements are visible (I do like this bit, the boards that make up Homeboard are quite pretty).

Mechanics

The build uses an Ikea picture frame, but replaces the front plate with my laser-cut front.

- The Ikea frame is great for this, it's built to support a front plate of 3-6mm, fitting a perspex sheet ferpectly.

- I'm happy with the display corner clips, too. You can see in the picture they hold the display, but are not too obtrusive (only partly due to the clips being transparent). Additionally, they are great to clip on small boards with no mount holes, like the radar sensor (top left in the picture).

- The ribbon connection to the display is hell. The position is awkward, and I can't fit it with a short (2cm) cable. I used a long one (15cm) but it looks untidy.

- Don't overtighten display screws! It's easy to put too much pressure and damage either the two perspex sheets, or the sandwiched display in the middle. I found for a 3mm perspex sheet with a laptop display, 10mm m2 screws loosely tightened (?) work best.

- If you use my mechanical drawings, be careful: between ID V1 and this one, there was bitrot in my svg, and the screws in the pi don't align anymore. Also, the display hole isi about 2mm too big for my panel, and I don't know why (my last cut it was 2mm to small!)

The back of the frame:

Some things I need to improve:

- Ribbon, long or short, placing is super hard. For V2 of this ID, I need to think of a better placement

- In fact, mounting everything to the front panel was a big mistake. It means that mounting things is awkward, because I need to work with a big panel. Any wiring mistake means I need to unmount the board, fix, test, remount. It's much much MUCH easier if I mount all the boards to a single main perspex board, then mount that to the main frame.

- Having a main board with alternative mount position should make it easier to make mounting the ribbon cable less terrible. I need to move the edp board 20mm to the right in this ID, but it's much easier if I don't need to carefully align this before I cut it.

- The corner clips are awesome! I can even use to hold sensors without a screw hole. Here I mounted the mmwave sensor (with no mount screw holes) using one of the corner clips.

- This doesn't work for the eInk display, unfortunately. I still need to figure out how to mount the eInk display without using tape.